Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii

Taxa on This Page

- Bandringidae X

- Ctenacanthidae X

- Ctenacanthiformes

- Elasmobranchii

- Euselachii

- Hybodontiformes X

- Phoebodontidae X

- Xenacanthida X

Undoubtedly the twisted tale of the genus Ctenacanthus Agassiz, as told by Maisey (1981), presents many deep issues in the history of science which serious minds may ponder at length. However, even Maisey's dry writing voice cannot disguise the sheer scientific slapstick of the story. Like a medieval farce, it allows us paleontological peasants to enjoy the spectacle of our betters doing pratfalls and splitting their trousers in public places.[1] But nothing ruins a good story like learnèd commentary.

The genus Ctenacanthus was originally erected, so to speak, by Louis Agassiz in 1837 [2]. The type specimen is a fin spine from the Lower Carboniferous Avon Gorge near Bristol in England. Agassiz's diagnosis is not a model of clarity. Maisey quotes extensively from the original (in French). The following translation attempts to preserve the flavor and sentence structure of the original:

The genus Ctenacanthus was originally erected, so to speak, by Louis Agassiz in 1837 [2]. The type specimen is a fin spine from the Lower Carboniferous Avon Gorge near Bristol in England. Agassiz's diagnosis is not a model of clarity. Maisey quotes extensively from the original (in French). The following translation attempts to preserve the flavor and sentence structure of the original:

"The Ctenacanthus [specimens] are some enormous, very compressed rays, having a large base but with a cavity smaller than that of Oracanthus. The portion of the these rays hidden in the flesh seems to have been considerable. On the posterior edge one sees some small spines. The surface is ornamented with longitudinal striations, more closely spaced than those of Hybodes, pectinate, which is to say transversely crenelated and projecting in the shape of teeth which alternate from one series to the other, but which seem to continue ['semblent continuer'] because of their diagonality ['obliquité']."

To which one may well respond, "Huh?", "Eh?", "Quoi?", "¿Que?", or some similarly inciteful phrase. Based on Maisey's discussion of the holotype of the type species, C. major, it would appear that there are no posterior "spines," although there may be a pronounced longitudinal ridge running along the center of a convex posterior surface. The discussion of the "pectinate" surface apparently refers to the zipper-like lateral interdigitation of the small tubercles which make up the closely-spaced striations covering the upper anterior surface.

Unfortunately, the holotype was probably never in really good condition -- even before it was recovered from near ground zero after the Bristol City Museum was bombed during World War II. (This event is also discussed in connection with the Sauropodomorpha). According to Maisey, Agassiz was probably also homogenizing the holotype of C. major with some generally similar, but not identical, spines which he obtained about the same time. However, these specimens disappeared, possibly well before the War.

On the strength of this diagnosis, Agassiz referred a number of other materials to the genus Ctenacanthus. These include, inter alia, C. brevis (a spine he never saw and which he described based on a drawing by someone else), C. ornatus (probably an acanthodian), and C. tenuistriatus (at least part of which has also disappeared). In the following years, a number of other specimens were referred to Ctenacanthus, including many with concave posterior surfaces or broad, enamelled striations, as well as materials which had no conceivable relation to the type, such as Russian cephalopods.

Things rocked along for some years in this fashion, including random specimens popping in and out of existence like quantum virtual particles, until 1873, when Newberry published an emended diagnosis. Being a careful, modern sort of researcher, Newberry not only diligently reviewed Agassiz's diagnosis, but procured two specimens of C. major for his personal inspection. Unfortunately, by some preposterous coincidence, not only were both specimens mis-identified, but they both turned out (much later) not to be Ctenacanthus at all. Instead, it appears that they were both remains of Sphenacanthus. This genus had also been described by Agassiz, but the holotype material was so poor that Newberry apparently did not recognize the resemblance. Sphenacanthus spines are quite unlike those of Ctenacanthus and "have irregular, widely spaced ribs, sometimes with scattered tubercles but never closely pectinated like those in C. major, and the spine is concave or flat posteriorly." Maisey (1981: 13).

Things rocked along for some years in this fashion, including random specimens popping in and out of existence like quantum virtual particles, until 1873, when Newberry published an emended diagnosis. Being a careful, modern sort of researcher, Newberry not only diligently reviewed Agassiz's diagnosis, but procured two specimens of C. major for his personal inspection. Unfortunately, by some preposterous coincidence, not only were both specimens mis-identified, but they both turned out (much later) not to be Ctenacanthus at all. Instead, it appears that they were both remains of Sphenacanthus. This genus had also been described by Agassiz, but the holotype material was so poor that Newberry apparently did not recognize the resemblance. Sphenacanthus spines are quite unlike those of Ctenacanthus and "have irregular, widely spaced ribs, sometimes with scattered tubercles but never closely pectinated like those in C. major, and the spine is concave or flat posteriorly." Maisey (1981: 13).

Given such contradictory indications, it is not surprising that Ctenacanthus became a nearly meaningless taxon. In the following decades any number of bits and pieces were referred to Ctenacanthus. It was even proposed that Ctenacanthus and Hybodus were synonymous. Things might have continued indefinitely in this way but for the discovery and gradual correlation of body fossils from the Cleveland Shale and elsewhere, as well as the careful sorting out of Late Paleozoic sharks by workers such as Maisey, Zangerl, and Lund. --ATW 010812

Notes: [1] The egregiously phallic morphology of the typical Ctenacanthus spine certainly adds something to the resemblance. [2] Maisey's citation is to Agassiz, L (1833-1844), Recherches sur les Poissons Fossiles. Neuchatel, 5 vv., 1420 pp.

Descriptions

Radiated in D and J. Primitively (i.e. in Paleozoic spp.); fusiform; mouth terminal; teeth from scales, usually cladodont (single large cusp); teeth have 3 enameloid layers; 5-6 gill slits; cleaver-shaped palatoquadrate, amphistylic support of palatoquadrate on braincase directly & per hyomandibula); trend: loss of direct connection (=hyostylic); posteriorly directed hypobranchials; vertebrae have arcualia inserted into strongly calcified centra; fin spines from same structure, usually associated with dorsal fins; 1-2 dorsals; heterocercal with superficial symmetry; fins supported by basals and radials to margin (plesodic); claspers (multiple convergent structures); tribasal pectoral; scales from fusion of lepidomoria,simple trilaminar with pulp; (cyclomorial pattern, as opposed to placoid).

Links: Sharks - What is a Shark?- Enchanted Learning Software; Shark Classification; subcl96.htm; Richard Ellis Gallery: Classification of Sharks. ATW010918.

Xenacanthida:

Xenacanthida:

Diplodus teeth, strongly forked; lg dorsal cephalic spine; optic-otic lateral fissure in braincase (odd for Chondrichthyes); elongate dorsal from head to tail; unforked(?) caudal; 2 anal fins. Convergent w Sarcopterygii in loss of radials ant to metapterygium & development of metapterygial radials! Fresh water; estuarine refugia by Early Permian.

Links: Prehistoric World Images - Carboniferous period - Xenacanthus decheni; "Fish don't have tusks"; Class-Chondrichthyes some old, but useful cites); Hampe very brief abstract on new genus); Devonian Times - More about Chondrichthys informative paragraph); Einhornmagie.de - Wissenschaft - Paläontologie. ATW030919.

Ctenacanthiformes: Ctenacanthus + modern sharks. Most authors probably define this taxon as Ctenacanthus > modern sharks. However, that definition leaves the contents of the group rather vague.

Range: from the Middle Devonian.

Phylogeny: Elasmobranchii: Xenicanthida + *: Bandringidae + (Phoebodontiformes + (Ctenacanthidae + Euselachii)).

Characters: cladodont teeth; cleaver-shaped palatoquadrate; broad otico-occipital region of braincase; pectinate ornamentation of dorsal fin spines; spines flat or concave posteriorly; central cavity of spines close to posterior face; 1st dorsal supported by a basal, with radials few or absent; pectoral fin basal cartilage rods fused to form 1-2 larger basals; uniserial (?? may refer to long metapterygium) pectoral fins; one anal fin; compound scales made up of numerous odontodes on a single base.

Links: Liste de genres.

Bandringidae: Bandringa. Small ctenacanthiforms with hugely elongated rostra.

Bandringidae: Bandringa. Small ctenacanthiforms with hugely elongated rostra.

Range: upC of NAm.

Phylogeny: Ctenacanthiformes: * + (Phoebodontidae + (Ctenacanthidae + Euselachii).

Characters: <12 cm; head and rostrum probably dorsoventrally compressed; very small, cladodont teeth; very long rostra; Meckel's cartilage of "normal" length; mouth subterminal; orbits large; fin spines of very uneven size, with anterior fin spine smaller; anal fin present; caudal fin somewhat heterocercal but without definite ventral lobe; pectoral fins much larger than pelvic fins; no dermal denticles?; probably fresh water genus.

Image: (A) Bandringa herdinae and (B) B. rayi. from Zangerl (1981).

Notes: Zangerl (1969) argues that B. rayi is probably a very immature individual based on lack of calcified skeletal elements, lack of dermal denticles, and oversized head. ATW010808.

Phoebodontidae: Phoebodus

Phoebodontidae: Phoebodus

Range: Early Devonian to Late Triassic worldwide. This range is based on teeth.

Phylogeny: Ctenacanthiformes:: * + (Ctenacanthidae + Euselachii).

Characters: broad head, probably with blunt snout; mouth probably terminal; cladodont teeth with central cusp same length as laterals & laterals angled away from central cusp at 30-40°; teeth fairly small; palatoquadrate (with tooth wells) ventrally & laterally expanded; lower jaws very deep posteriorly (possibly broad attachment for jaw adductors); jaws projected far beneath braincase; orbits very large with small undershelf and very broad supraorbital shelf; braincase small and blunt anteriorly; large otic process of braincase; otic process probably attachment for large jaw adductor; posteroventral surface of otic process calcified to form articular surface (for hyomandibula? and/or palatoquadrate?); palatoquadrate probably also articulated with postorbital process; ethmoid articulation weak or absent; hyoid arch also enlarged; hyomandibula meets ceratohyal medial to Meckelian - palatoquadrate articulation; ceratohyals extend anteriorly medioventral to Meckelian, meeting at a basihyal just below the mandibular symphysis; jaw may have been somewhat protrusible; pectoral fins dibasal; pectoral radials divided; first dorsal finspine larger than second; spines probably very deeply set (ornamented portion is short); integument densely covered with compound denticles.

Note: [1] known mostly from isolated fragments. [2] The characters above take the reconstruction by Prof. Barbara Stahl (1988) at face value. Stahl's reconstruction is based on painstaking and elegant model-building from radiograms. It is very convincing. However, both the technique and the material have limitations; and the reconstruction is necessarilly subject to some uncertainty. It would be interesting to see what could be done with more modern radiographic techniques i.e. CAT) and image manipulation software. [3] Note that the ethmoid region and nasal capsules were not preserved in the specimen used to generate the image. No attempt has been made to reconstruct them in the image.

Ctenacanthidae: basal (?) ctenacanthiforms, mainly Ctenacanthus.

Ctenacanthidae: basal (?) ctenacanthiforms, mainly Ctenacanthus.

mostly upD-upC, but depends on exact contours of clade. Most broadly, mD-lw(?)T. Most narrowly, lwC only. Maisey (1981) seems to prefer the narrowest range for Ctenacanthus.

Phylogeny: Ctenacanthiformes::: Euselachii + *.

Characters: quadrate articulates only with ethmoid; calcified ribs absent; caudal fins bilobate and deeply forked; no basals or radials in dorsal lobe of caudal fin; scapulocoracoid tapers distally and is strongly concave anteriorly; enameloid on spines; spine is deeply set and supported by basal cartilidge; spines gradually tapering and recurved posteriorly; anterior face of spine narrow and rounded; posterior face of spine with pronounced median ridge, separated from edges of posterior face by flat or slightly concave area; spine 2-3X deep as broad in cross-section; spine ornament of closely-spaced longitudinal lines; spine lines made up of very small transverse tubercula which projects laterally; tubercula of adjacent lines may interlock in a zipper-like fashion; spine largely trabecular dentine, with weakly developed internal lamellar layer; anal fin with trace of tribasal modern structure; propterygium and mesopterygium on pectoral fins; in more advanced forms, radials not to margins, with ceratotrichia; integument of compound dermal denticles.

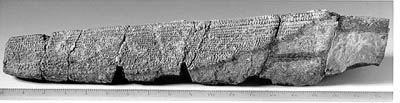

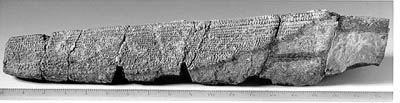

Image: Ctenacanthid spine AMNH 19236, courtesy of Dr. Wayne Itano.

Image: Ctenacanthid spine AMNH 19236, courtesy of Dr. Wayne Itano.

Links: A Listing of Fossil Sharks and Rays of the World; Ctenacanthidae; \Fish don't have tusks\; Ctenacanthus; Devonian Times - Ctenacanthus sp.; Kansas Ctenacanthus; Ural.htm; Ancient Sharks; Untitled Document; Condrichthyes Page (doesn't look like Ctenacanthus).

References: Maisey 1981); Zangerl (1981). ATW020921

Hybodontiformes: Hybodus, Acrodus

Characters: 1-2 pairs of hooked cephalic spines [C88].

References: Carroll (1988) [C88]. ATW991008.

The genus Ctenacanthus was originally erected, so to speak, by Louis Agassiz in 1837 [2]. The type specimen is a fin spine from the Lower Carboniferous Avon Gorge near Bristol in England. Agassiz's diagnosis is not a model of clarity. Maisey quotes extensively from the original (in French). The following translation attempts to preserve the flavor and sentence structure of the original:

The genus Ctenacanthus was originally erected, so to speak, by Louis Agassiz in 1837 [2]. The type specimen is a fin spine from the Lower Carboniferous Avon Gorge near Bristol in England. Agassiz's diagnosis is not a model of clarity. Maisey quotes extensively from the original (in French). The following translation attempts to preserve the flavor and sentence structure of the original: Things rocked along for some years in this fashion, including random specimens popping in and out of existence like quantum virtual particles, until 1873, when Newberry published an emended diagnosis. Being a careful, modern sort of researcher, Newberry not only diligently reviewed Agassiz's diagnosis, but procured two specimens of C. major for his personal inspection. Unfortunately, by some preposterous coincidence, not only were both specimens mis-identified, but they both turned out (much later) not to be Ctenacanthus at all. Instead, it appears that they were both remains of Sphenacanthus. This genus had also been described by Agassiz, but the holotype material was so poor that Newberry apparently did not recognize the resemblance. Sphenacanthus spines are quite unlike those of Ctenacanthus and "have irregular, widely spaced ribs, sometimes with scattered tubercles but never closely pectinated like those in C. major, and the spine is concave or flat posteriorly." Maisey (1981: 13).

Things rocked along for some years in this fashion, including random specimens popping in and out of existence like quantum virtual particles, until 1873, when Newberry published an emended diagnosis. Being a careful, modern sort of researcher, Newberry not only diligently reviewed Agassiz's diagnosis, but procured two specimens of C. major for his personal inspection. Unfortunately, by some preposterous coincidence, not only were both specimens mis-identified, but they both turned out (much later) not to be Ctenacanthus at all. Instead, it appears that they were both remains of Sphenacanthus. This genus had also been described by Agassiz, but the holotype material was so poor that Newberry apparently did not recognize the resemblance. Sphenacanthus spines are quite unlike those of Ctenacanthus and "have irregular, widely spaced ribs, sometimes with scattered tubercles but never closely pectinated like those in C. major, and the spine is concave or flat posteriorly." Maisey (1981: 13).

Image: Ctenacanthid spine AMNH 19236, courtesy of Dr. Wayne Itano.

Image: Ctenacanthid spine AMNH 19236, courtesy of Dr. Wayne Itano.