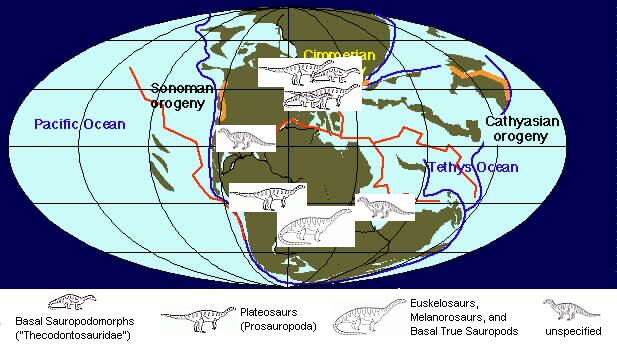

Distribution of Norian sauropodomorphs

map by Dr. Ron Blakey

| Late Triassic epoch | ||

| Mesozoic: Triassic Period |

Norian Age - 5 |

| Carnian | Middle Triassic | Norian 1 | ||

| Rhaetian | Early Jurassic | Timescale |

|

|

Distribution of Norian sauropodomorphs map by Dr. Ron Blakey |

The ecological turnover and dominance of the Archosaurs, specifically the dinosaurs, is particularly evident in the early representatives of the clade of herbivorous dinosaurs known as the Sauropodomorpha. Although small and insignificant throughout the Carnian and early Norian, during the middle Norian these early sauropodomorphs underwent an astonishing evolutionary radiation. It is not at all clear what triggered this. A combination of factors like vegetation and climate change (the prosauropods were better able to cope with aridity than the dicynodonts; although this assumes that there really was a global climate change in the Norian (which Olsen et al seem to indicate was not the case). It could hardly have been the absence of predators because large Rauisuchians were already present

These animals - thecodontosaurs, plateosaurs, and their kin - were all of a paraphyletic assemblage of early plant eating dinosaur formerly known as "Prosauropods", although the more accurate, if rather unwieldy term Basal Sauropodomorphs is used now. Prosauropod literally means "before the sauropods", because they were the ancestors and grand-uncles of the gigantic sauropods like Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus. Indeed they resembled much smaller and lightly built versions of those better known animals. Previously a rather minor element of the tetrapod fauna, they underwent an evolutionary radiation during the Middle Norian, but it was really in the Late Norian and Rhaetian that they came to prominence. There seem to have been several different lineages, including persistently primitive thecodontosaurs (which don't seem to have changed much since the middle Carnian), the Prosauropoda proper, and the Sauropoda proper and their immediate ancestors (of which Anchisaurus is the most primitive albeit not the earliest known representative). As the Norian advanced the latter two of these clades diversified, with Prosauropods becoming Plateosaurs, Euskelosaurs, and Riojasaurs, and Anchisaur grade Proto-Sauropoda becoming Euskelosaurs, melanorosaurs, blikanosaurs, and True Sauropods.

|

|

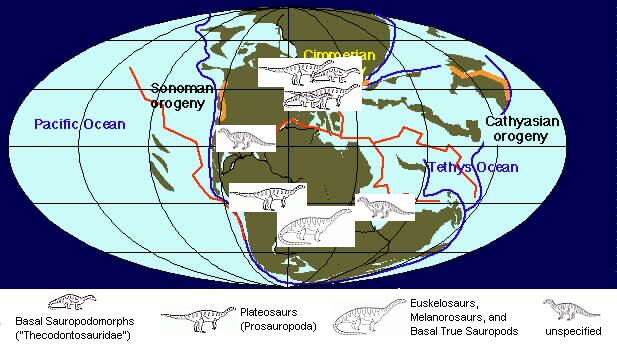

Thecodontosaurus illustration copyright © Satoshi Kawasaki - original page |

Thecodontosaurus antiquus is a small and very primitive dinosaur, near the base of the sauropodomorph tree, only a little more advanced then the late Carnian Saturnalia. The neck is short for a sauropodomorph, and the skeleton bears many primitive features. It is best known from Welsh Norian-Rhaetian "fissure fillings" but is also known from Durdham Down near Bristol in England, the late middle Norian (Middle Stubenstein) of southwest Germany [Benton 1986] (T. hermannianus), and has also been tentatively reported from Poland [ref Justin Tweet - Sauropodomorpha]. A very similar animal, Agrosaurus macgillivrayi Seeley, 1891, once thought to be the only known Australian dinosaur fossil from the late Triassic, later turned out to be mislabeled, and actually comes from England, and is a junior synonym of Thecodontosaurus antiquus. A new species T. caducus, has recently been described [Yates_2003). The presence of equivalent German forms like Saltoposuchus and Thecodontosaurus is sometimes used to argue for a Norian date for the English and Welsh fissure fillings but there is no way to date these for certain.

Efraasia, from the late middle Norian (Middle Stubenstein) of southwest Germany, is a closely related, slightly more advanced form than Thecodontosaurus, that is more than twice the linear dimensions. thecodontosaur grade dinosaurs then were an important part of the late Triassic fauna, although they do not seem to have survived the end-Triassic extinction. This persistently primitive type continued to exist quite happily alongside its giant plateosaur cousins, possibly inhabiting a specific niche environment in Europe.

Thecodontosaurus hermannianus

Late Middle Norian

?

Medium-sized Herbivore

Known only from the partial maxilla (upper jaw bone), this basal sauropodomorph is too fragmentary to classify further, and there is nothing that specifies it belongs to Thecodontosaurus

Efraasia minor

Middle Stubensandstein

Baden-Wurttemberg, SW Germany

Late Middle Norian

6 meters

Dominant Large Herbivore

Thecodontosaurus antiquus

1.5 (juvenile?) to 2.6 meters

Dominant Medium-sized Herbivore

Thecodontosaurus caducus

fissure fill in Pant-y-ffynnon Quarry

Pant-y-ffynnon Quarry, South Wales

?Middle or ?Late Norian or ?Rhaetian

Medium-sized Herbivore

known from juvenile specimens

|

|

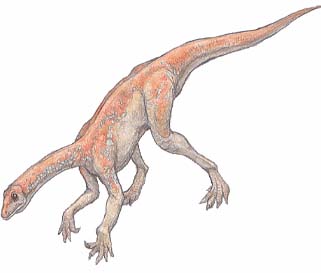

Plateosaurus illustration copyright © Satoshi Kawasaki - original page |

The animal traditionally referred to as Plateosaurus engelhardti Meyer, 1837 might actually be a different species, Plateosaurus longiceps (see notes on Plateosaurus). Regardless of what scientists finally decide its name should be, is the archetypal prosauropod, the best known German dinosaur, and, with Coelophysis, the best known Triassic dinosaur. It is known from the late Norian (Oberer Stubensandstein and Knollenmergel; Upper Löwenstein and Trossingen Formations) where it seems to have completely supplanted the earlier and more diverse Middle Norian (Mittlerer Stubensandstein) prosauropod fauna. This predominance may however be a preservation bias or the result of local conditions, and suggest immigration from elsewhere [Benton 1986]. Remains have been found from over 30 localities in an area of about 500km by 50km, including Franconia, Wuerttemberg, Thuringia and Saxonia-Anhalt. In Trossingen about 60 Plateosaurs have been found (approx. 100 finds). Altogether over 100 partial and complete skeletons and ten skulls are known, many of which have been attributed in the past to different species and even genera. Plateosaurus has also been reported from the Switzerland, France, and Sweden, with a range possibly extending into the Rhaetian [ref. Justin Tweet - Sauropodomorpha]. It seems that the Plateosaurs were the predominant megaherbivores of their time, a role that continued into the following, Rhaetian age with the South American Riojasaurus.

Unaysaurus tolentinoi

Catturita Formation

southern Brazil

Latest Carnian/early Norian

2.5 meters

30 kg

Medium-sized Herbivore

skull and partial skeleton known

Plateosaurus gracilis

Lower and Middle Stubensandstein

Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany

Middle Norian

4 to 6.5 meters

110 to 400 kg

Large Herbivore

also known as Sellosaurus; this is probably a more correct name cladistically speaking, since the genus Plateosaurus is almost certainly paraphyletic

Plateosaurus longiceps

Late Middle to Late Norian (to Rhaetian?) of Upper Stubensandstein of SW Germany, and of Knollenmergel of Thuringen, Germany

8 meters

1300 kg

Dominant Large Herbivore

a gracile form, includes the famous Trossingen plateosaur

Plateosaurus engelhardti

Knollenmergel

Bavaria

Late Norian

8 meters

1500 kg

Large Herbivore

the most heavily built and the most quadrupedal of the three species.

Ruehleia bedheimensis

Trossingen Formation = Knollenmergel

South Thuringia, Germany

Late Norian

8 meters

Large Herbivore

originally referred to Plateosaurus plieningeri,

|

|

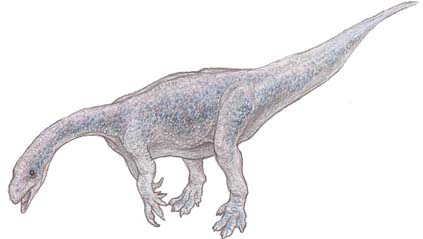

Melanorosaurus illustration copyright © Satoshi Kawasaki - original page |

Melanorosaurus readi was a large (7.5 meters long) proto-sauropod. Some individuals, perhaps of a related species, are thought to have reached 12 to a whopping 15 meters in length, which would make them the largest land animals of their time, and indeed of the entire Triassic. The melanorosaurs lived alongside other sauropodomorphs like 8 meter long Euskelosaurus browni, and the earliest known sauropod Antetonitrus ingenipes, some 10 meters or more in length. The giants had arrived.

Great size has forced this gentle herbivore down on all fours; unlike Plateosaurus it could not walk on its back legs even if it wanted to do. The hips have four sacral vertebrates, as opposed to three in Plateosaurus and Euskelosaurus, making them stronger and better able to transfer force to and from the powerful hind legs. The femur or thigh bone is straight too, like an elephant's, to help take the weight, and Melanorosaurus certainly would certainly have matched an African elephant in size (assuming an 8 meter Plateosaurus weighed 1500 kg, and scaling up from there), while a 15 meter individual would have equaled a modest sized sauropod in bulk.

Traditionally, Melanorosaurus, Riojasaurus, and a number of other early four-legged forms were grouped in the family Melanorosauridae, but Riojasaurus is now considered a more primitive form.

|

Euskelosaurus browni illustration © 2001 Vince R Ward - Prehistoric Pages |

Euskelosaurus browni was a large (8 to 10 meters long) but fairly lightly built early sauropodomorph that was the commonest medium to large animal in its environment. It is known from the Lower Elliot formation (Late Norian) of South Africa, Lesotho, and Zimbabwe, and it clearly filled the same ecological role in Southern Gondwana that Plateosaurus did in central Laurasia (Europe and Greenland). It is quite likely that these animals were contemporaries, representing a worldwide sauropodomorph Plateosaur-Melanorosaur-Protosauropod) community that continued from the Late Norian to the end of the Rhaetian, where there was an ecological turnover and a more diverse (but still dinosaur-dominated) biota took over.

Despite being such a common animal, the evolutionary relationships of Euskelosaurus are not clear. Originally it was considered a Prosauropod closely related to Plateosaurus, but more recently it has been considered a proto-sauropod [see Mortimer 2003 for suggested cladogram]). There is no doubt that the sauropodomorphs were a diverse and vibrant clade at this time, with a number of primitive and advanced lineages evolving in parallel.

|

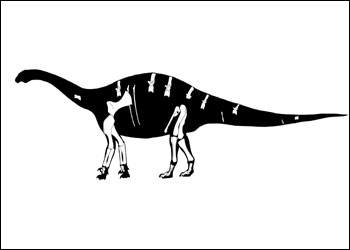

Skeletal diagram of the remains found for Antetonitrus illustration © Adam Yates |

Antetonitrus ingenipes, from the Lower Elliot Formation of South Africa, is the earliest known, and most primitive, true sauropod. This large (8 to 10 meters long), heavily built animal shows a mixture of primitive and advanced characteristics. Its fore and hind legs are of almost length and the foot is very short, indicating a slow, fully quadrupedal posture. Yet the fore-feet are also prosauropod-like, in that the thumbs retain a grasping ability. Possibly these large herbivores would rear up on their hind limbs, and use their forefeet and claws to pull down the branches of trees.

New dinosaur gives glimpse into the past

|

|

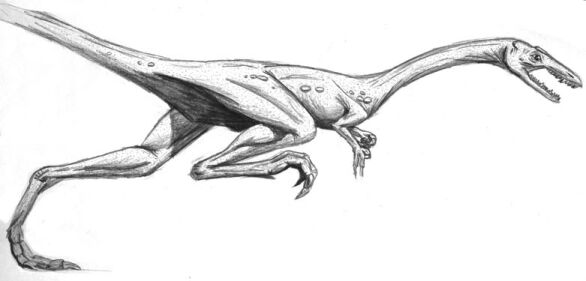

Procompsognathus triassicus image © Robert Gay |

Procompsognathus triassicus, known from the Middle Stubensandstein of Württemberg, Germany, is the most primitive (although not the earliest) of the Podokesaur (Coelophysid) theropods that were an important element in the Latest Norian through to Toarcian terrestrial environments. It possessed relatively broad pubes (hip-bones), a primitive feature that distinguishes it from all other Theropods. This was a small, active, lightly built animal, about a meter in length, and may be related to the early Jurassic Segisaurus. If the latest Carnian Saltopus elginensis is a Coelophysid (which is by no means certain) it would represent a good ancestral type

|

illustration © 2001 Vince R Ward - Prehistoric Pages |

From the latest Carnian through to the later Early Jurassic (Toarcian), small podokesaurs played an important part throughout Pangea as small-medium sized terrestrial predators. Many of these belong to the genera Coelophysis, so far known only from the SW USA. A number of types from the latest Carnian and Norian, previously included in the genus Coelophysis, have since been given different names but are closely related in structure, appearance, and obviously, habits and lifestyle. Syntarsus is a more advanced form with fused ankle-bones, has a much wider distribution - in the Norian it is known from both New Mexico and Wales (Pant-y-ffynnon fissure filling), and in the Hettangian from Lesotho and South Africa (Upper Elliot Formation). Many (although not necessarily all) of the small three-toed footprints that are called Grallator were probably made by these animals.

|

|

The Late Norian theropod Liliensternus liliensterni, artwork © M. Shiraishi |

At 5 1/2 meters in length, Gojirasaurus quayi is the earliest known large theropod dinosaur. It is, appropriately, named after Godzilla (using the correct, Japanese pronunciation). Named after Godzilla (using the correct, Japanese pronunciation) this is the earliest known large theropod dinosaur. [Carpenter 1997]

Known from two (apparently, more on this shortly) sub-adult specimens, Liliensternus liliensterni is intermediate between the small (2.5 meters) and earlier latest Carnina/earliest Norian Coelophysis and the large 6 to 7 meters long) and later (Jurassic: Sinemurian) Dilophosaurus in anatomy. These were large graceful bipedal predators of the subfamily Dilophosaurinae (= Halticosaurinae). Liliensternus is probably a descendent from the earlier large podokesaurs like the upper Chinle Gojirasaurus; it represents a type that seems to have persisted with little change from the Middle Norian to the late Rhaetian, and which in turn - surviving the end-Triassic mass extinction, gave rise to the large dinosaurian carnivores of the Jurassic. They were also the first of the great dinosaurian carnivores.

Liliensternus has been found in association with Plateosaurus [Rauhut and Hungerbuhler 1998], and whilst healthy adult Plateosaurs were too big for the theropod to take on, the young, the old, or the sick or injured were another matter. Liliensternii probably stalked and followed plateosaur herds, waiting for an opportunity. In this they followed a different feeding strategy to the lie-in-wait rauisuchian predators like Teratosaurus.

Although longer than most rauisuchian thecodonts, Gojirasaurus and Liliensternus were more lightly built; essentially scaled up versions of a small animal like Coelophysis. These large coelophysids also seem to have been rather less common than the thecodont (pseudosuchian) carnivores, which remain the main terrestrial terrestrial predators through till the end of the Triassic.

The traditional interpretation of animals like Gojirasaurus and Liliensternus is that they are sub-adults, as indicated by certain qualities in the skeleton, and that the full-grown theropod was some 7 meters or so in length (say the size of a large dilophosaurus). The problem here is that no large carnivore footprints (Eubrontes) occur until the earliest Jurassic [Olsen et al 2002]. So if there were half-tonne Norian theropods, where are their footprints? Instead, we see a sudden increase in theropod footprint size from small to medium during the Mid Norian (just at the time that Gojirasaurus appeared) and then another increase from medium to large at the earliest Hettangian (earliest Jurassic). I would suggest, as away of resolving this quandary (disclaimer - this is intended as rampant speculation only!), that maybe the 5 meter long so-called sub-adult Gojirasaurus and Liliensternus skeletons really were of adult animals, and that these creatures had neotonous features. Then, with the extinction of rauisuchians during the end Triassic, theropod dinosaurs quickly evolved to larger size and captured the ecological niche of top predator previously held by the "thecodonts"

|

|

Did climate change and increasing aridity kill off the once-abundant dicynodonts, as this image from the classic series Walking with Dinosaurs indicates? Photo by Ian Macdonald from Walking With Dinosaurs - Placerias; © BBC/ABC from Walking with Dinosaurs |

During the Norian the lived the last of the placerine Dicynodontia, members of the family Kanemyeriidae and the last known survivors of a long and successive lineage that stretched back to the Middle Permian. These large terrestrial herbivores weighed over a tonne each. It is possible that they were killed off by the increasing aridity which favoured the archosaurian metabolism, and may have even been forced to migrate long distances, as shown in the above still from the superb BBC series Walking With Dinosaurs . However Olsen et al 2001 argues that the apparent aridification of the Norian is just a sampling bias, and that these typically Carnian faunas continued into the Norian without suffering any decline. Certainly the traversodontid cynodonts continued right up until the end of the Triassic.

|

|

Jachaleria colorata; length of lower jaw 40 cm illustration from Bonaparte 1970

|

Jachaleria colorata |

Norian Dicynodonts are best known from South-west Gondwana (Argentina). A kannemyeriid skull and complete jaws, identified as a new species by Bonaparte 1971 who named it Jachaleria colorata, is known from the Basal Los Colorados Formation, La Rioja Province Argentina (considered by Lucas 1998 to be Apachean = Rhaetian, but I would suggest more likely a Norian age). This was a large animal, the length of the lower jaw 40 cm [Bonaparte 1970 p.681] According to Bonaparte, J. colorata is the only tetrapod collected from the base of the Los Colorados Formation, which immediately overlies the (late Carnian) Ischigualasto. Lucas, 2001b states that Jachaleria colorata is a synonym of Ischigualastia. However, other recent papers (e.g. [Leal et al 2004] consider Jachaleria a separate genus.

A similar form, Jachaleria candelariensis, is known from the early Norian [Scherer 1994, Leal et al 2004] (although Lucas 1998 suggests the date is Adamanian (latest Carnian)) Upper Caturrita Formation, Brazil. J. candelariensis is found together with the herbivorous cynodont Exaeretodon sp. In as much as Jachaleria (= Ischigualastia?) is reported from both the Upper Caturrita Formation (Early Norian?) and the basal Los Colorados (Late Norian?) it seems that these large animals continued quite happily in Southwest Gondwana at this time.

Other records of Norian kannemeyeriids include a dicynodont toe is known from the early or middle Norian Deep River Basin, Newark Supergroup, North Carolina Sues et al 2001, and footprints ({entasauropus") from the Late Norian Lower Elliot formation [Lucas and Hancox, 2000].

BBC - Walking with Dinosaurs - Fact Files - Placerias

|

Traversodontid drawing © 2001 Vince R Ward - Prehistoric Pages |

It was once thought that the herbivorous Traversodontid Cynodonts died out at the end of the Carnian. With the discovery of Plinthogomphodon herpetairus Sues et al 1999, this is now known not to be the case. The discovery of surprisingly common remains of this smallish (cat sized) animal in the Middle Norian Newark Supergroup, North Carolina (at the time equatorial Pangea) indicates that, unlike their dicynodont distant relatives, the Traversodontids were not affected by the Carnian-Norian turnover. Plinthogomphodon seems to be similar to the slightly earlier Boreogomphodon from the Latest Carnian of Virginia, and hence may well be a descendent or close relative of that animal.

A larger animal Scalenodontoides macrodontes is known from the Lower Elliot and Molteno Formations of Lesotho and South Africa (probably Late Norian). It shows that decent-sized traversodonts continued into the latest Norian at least, although these animals were no longer as abundant as in the past. [see also Trevor Dykes Triassic Gomphodonts]

|

|

Traversodontid drawing © 2001 Vince R Ward - Prehistoric Pages |

Pseudotriconodon chatterjeei Lucas and Oakes, 1988 was a member of the Dromatheriidae, related to the Latest Carnian Dromatherium and Microconodon. It lived several million years later, and somewhat to the east, being known from the Bull Canyon Formation, Chinle Group, East-Central New Mexico; Early or Middle Norian (Revueltian Age). These tiny shrew-like cynodonts, although poorly known, were probably an important part of the late Triassic terrestrial environment. In life they would have resembled small mammals, not reptiles. A related species, Pseudotriconodon wildi Hahn, Lepage & Wouters, 1984, is known from the fissure fillings of Saint-Nicolas-de-Port, France (Late Norian or early Rhaetian)

Godefroit & Battail 1997; Lucas 1998 p.370; Trevor Dykes Chiniquodontoidea