| Paleogeography | ||

| PALEOGEOGRAPHY | Pangea |

| Palaeogeography | Plate Tectonics |

History of discovery |

If you look at the outlines of continents - e.g. the east coast of South America and the west coast of Africa, you notice they fit together like a big jigsaw puzzle. In 1912 the father of the theory of continental drift, Alfred Wegener, cited geographical, geological, and paleontological evidence and proposed that some 200 million years ago the worlds continents were all joined into a single supercontinent which he called "Pangea" (all the Earth). As the sea floor spread Pangea broke up and the continents began to drift away from each another, finally assuming their present positions. Wegener's hypothesis languished until 1968, when empirical evidence of sea floor spreading was found, the old geological models overthrown, and a paradigm shift established continental drift as the mainstream understanding of the Earth.

The separate continents of the Paleozoic, after having drifted apart through the fragmentation of the supercontinent of Rodinia, around 650 million years ago (Ediacaran period) eventually drifted together again during the Paleozoic, colliding to form the supercontinent of Pangea during the Devonian and Carboniferous periods, some 350 million years ago. More specifically Pangea was assembled by the collisions of three main blocks, Gondwana, Euramerica, and Siberia, during Permo-Carboniferous time, around 350 to 260 million years ago. Various smaller blocks, especially in southeastern Asia, were late arrivals. In the initial collision between Gondwana and the northern continents, South America abutted central Euramerica. Modern Spain and central France are former pieces of Venezuela. Pangea was essentially complete by the Kungurian Age (late early Permian). A sliding motion then carried Gondwana 3500 kilometers westward, relative to the northern landmasses, until Africa was abutting North America by the Norian Age (Late Triassic), producing the classic Pangea configuration (E. Irving, Nature, Vol.270, 1977, p.304). [Nigel Calder, Timescale, p.264]

Pangea began to rift apart almost immediately. However, the process of separation was prolonged for some 250-300 million years, resulting in roughly the modern series of separate continental blocks in the early to Mid-Cretaceous, some 130-100 million years ago. However, for much of its long history the supercontinent was actually a series of large islands, separated from each other by shallow continental seas.

The hundred million years and more of Pangean history saw a succession of cosmopolitan animal dynasties spread over the entire supercontinent. Different families of amphibians and reptiles would arise, flourish for a while, and then die out, before being replaced by a new biota. The hot arid conditions that persisted over much of the supercontinent for all this time favoured reptiles over therapsids and mammals; hence all the large-bodied (and most small-bodied) ecological niches were filled by eureptilians, especially archosaurs, with amphibians continuing only in rivers and ponds, and synapsids becoming progressively smaller and less diverse, and finally nocturnal. Only during the later days of Pangea, in the Jurassic, did the tiny Mesozoic mammals diversify.

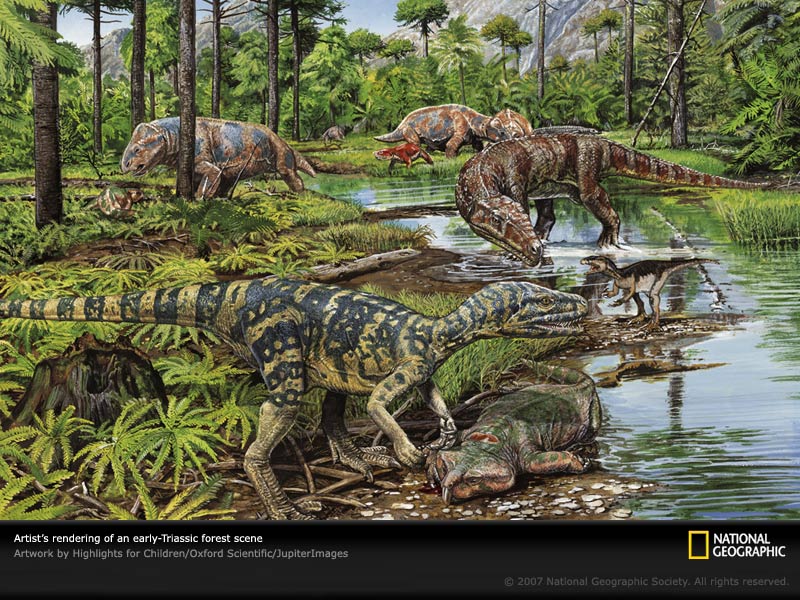

A Late Triassic (Carnian Age) scene, showing typical animals and plants that existed in what is now Argentina (Ischigualasto Formation). Similar communities existed across Pangea (of course, such animals were never crowded together this closely in real life). Following the extinction of the Permian therapsids due to the end Permian-extinction, most of the large animals that populated Pangea were archosaurs or archosauromorphs. In the foreground is the basal dinosaur Herrerasaurus, feeding on Scaphonyx a rhynchosaur. These were abundant medium sized herbivores (the one in the drawing is a little too small relative to Herrerasaurus). Near the stream is Eoraptor, a small very primitive theropod. During this time, dinosaurs were still quite small; at 4 meters, Herrerasaurus, was among the biggest of its kind. Behind Eoraptor is the huge predatory pseudosuchian Saurosuchus, which at 6 to 7 meters long was the dominant animal of its environment. In the background are several Kannemeyeriid dicynodonts of the genus Ischigualastia (= Placerias). These common herbivores were the biggest plant eaters until the rise of the dinosaurs. Near one of the dicynodonts is the herbivorous traversodontid cynodont Exaeretodon, the most common animal in this environment, and unfortunately drawn much too small in this illustration. Both Ischigualastia and Exaeretodon were therapsids, the last large representatives of lineages that dominated the land during the Middle and Late Permian. However, smaller mouse-sized cousins of Exaeretodon were at that very time evolving into mammals. To the right of the Ischigualastias and mostly hidden by Saurosuchus is the armoured aetosaur Stagonolepis, a smaller herbivorous cousin of Saurosuchus.

The plants include large trees (over 40 meters tall) called Protojuniperoxylon ischigualastianus, which may be related to Araucariaceae (Monkey-Puzzle Trees), cycads, seed-ferns, ferns such as Cladophlebis, and Sphenopsida (horsetails), which were probably the ecological equivalent of bamboo.

Original url: National Geographic, Artwork by Highlights for Children/Oxford Scientific/JupiterImages