Archaic Mammals: Creodonts

Taxa on This Page

- Hyaenodontidae X

- Oxyaenidae X

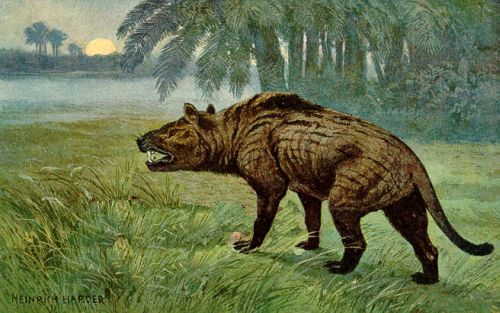

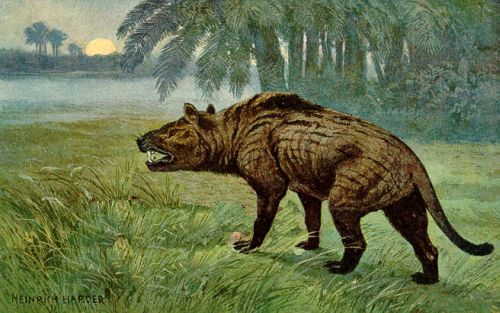

The ubiquitous Laurasian and African Late Eocene to Early Miocene apex predator Hyaenodon (Hyaenodontidae). While the smallest species were no bigger than a small dog, the biggest were the size of wolves or even bears. Previously included under the category of Creodonts, and considered ancestral to modern Carnivora, it now seems that these animals represented a distimnct lineage of early mammalian carnivores. Artwork by Heinrich Harder (public domain) |

"Creodonts": Carnivores by Association

By Christopher Taylor Catalogue of Organisms

As explained in an earlier post (which you may be interested in reading as a bit of background to this one), the earlier part of the Caenozoic (the current era of the earth's history) was home to a number of mammalian lineages of very mysterious relationships. Very few of the familiar orders around us today had yet put in an appearance, and instead the world was home to such oddities as pantodonts, tillodonts and dinocerates. Among the prominent carnivorous mammals of the time were a group known as the creodonts. Creodonts ranged in size from that of a small cat to lion- or bear-size species, and often converged in appearance with those animals. But what were creodonts?

Current authors regard the Creodonta as including two families, the vaguely cat-like Oxyaenidae and the largely dog- or hyaena-like Hyaenodontidae. Oxyaenids were found in North America and Europe during the late Palaeocene and Eocene, while hyaenodontids were found in Africa, Eurasia and North America from the Late Palaeocene to near the end of the Miocene, though they disappeared from North America not long after the end of the Eocene (Gheerbrant et al., 2006). Many authors have suggested a relationship with modern carnivorans (cats, dogs, weasels, bears, etc.), and they have been included with the latter in a superorder Ferae. Popular as this arrangement has been, however, there's just one small problem - there's not a shred of evidence to support it.

Part of the problem is that creodonts are a good example of what might be called "taxonomic drift". Imagine that an author establishes a taxon, and presents a list of organisms that he thinks belong to that taxon. A few years pass by, and the taxon is revised by another author, who excludes some of the originally-included species that he thinks belong elsewhere, and substitutes a few more species that he believes to be related to the remainder. Carry this on through a few subsequent revisions, with species being taken out and put in, and you may end up with a situation where nearly all of the original members of the taxon have been taken out, and the taxon name has become associated with a very different concept from its original intent. This can be horrendously confusing for later readers, because if they don't realise that this taxonomic drift has taken place, they may read things into older publications that their authors never intended.

Creodonta was originally established by Edward Drinker Cope in 1875 as a suborder of the Insectivora [1]. In his new suborder, Cope included three families - Oxyaenidae, Ambloctonidae (now included in Oxyaenidae - Gunnell, 1998) and Arctocyonidae (another contemporary family of carnivorous placentals, within which Cope also included what are now regarded as the Miacidae). The Hyaenodontidae were not part of the original Creodonta - at the time, Hyaenodon was regarded as a genuine carnivoran. Cope distinguished creodonts from carnivorans by the former's lack of a fused scapholunar bone in the wrist, their ungrooved astragalus, and their less-developed and smoother cerebral hemispheres (Cope, 1884). These features, it should be noted, are all primitive for placentals, but to Cope indicated the creodonts' position in the insectivoran grade. He nevertheless regarded creodonts as ancestral to carnivorans, with cats descended from Oxyaenidae and dogs from Miacidae (Cope, 1880). Later, Cope (1883) included Insectivora and Creodonta as separate suborders of his order Bunotheria, which also included the tillodonts, taeniodonts and prosimians [2]. Cope (1883) also redefined creodonts to include mammals without continuously-growing incisors and with trituberculate molars, which meant that in addition to the Oxyaenidae and Miacidae, Creodonta now included Mesonychidae, Leptictidae, moles and tenrecs (Arctocyonidae were transferred to the Insectivora). The Hyaenodontidae wormed their way in a year later (Cope, 1884).

Skull of the sabre-toothed creodont Machaeroides eothen. Gunnell (1998) places Machaeroides in Oxyaenidae. Photo by Photo by Ghedoghedo |

So right from the beginning, the question of what was a creodont was convoluted. Over the years, various families of "creodonts" were reassigned as their relationships became clearer. The Miacidae became regarded as true Carnivora. Arctocyonidae and Mesonychidae became included among the primitive ungulates (another confused mess, but that's a story for another year) and may be related to artiodactyls. Moles and tenrecs, of course, were reunited with their fellow modern insectivorans (though the tenrecs have recently had another falling-out). Eventually, the creodonts were whittled down to their modern content of oxyaenids and hyaenodontids, but, as pointed out by Polly (1996), "Hyaenodontidae and Oxyaenidae are currently grouped together in Creodonta because they are the only taxa that have not been removed from the group, not because there has been specific positive evidence proposed for their grouping". Those few characters the two families do share are also found in other, non-creodont mammals. As for their association with Carnivora, the two orders have been associated because they both possess shearing carnassial teeth. However, while the carnassials in Carnivora are formed by the last upper premolars and the first lower molars, those of Oxyaenidae are derived from the first upper and second lower molars, while hyaenodontids have two sets of carnassials formed by the first upper/second lower and second upper/third lower molars. Carnassials have also developed in other groups of mammals - notably the borhyaenoids, which are metatherians if not marsupials and so definitely not related to carnivorans. The only real reason creodonts have been associated with Carnivora for so long seems to be their prior inclusion of the genuinely carnivoran (or stem-carnivoran) miacids. It's a bit like when one of your friends brings an acquaintance of theirs to a party who just hangs around for hours with everybody being too polite to ask them to leave.

So, if they weren't related to Carnivora, can we say what creodonts were related to? Particularly in the case of Oxyaenidae, the answer is brief, simple and to the point: we really have not got a sodding clue. Whatever their ancestry might have been, oxyaenids were horribly derived little (or not so little) beggars - for instance, they had completely lost the third molars. Van Valen (1969) derived both oxyaenids and hyaenodontids from the Palaeoryctidae, particularly from the Cretaceous-Palaeocene Cimolestes, and other authors seem to have regarded the idea favourably, at least for the hyaenodontids (Polly, 1996; Gheerbrant et al., 2006). The main problem with this scenario, however, is that the Palaeoryctidae of Van Valen and other authors is itself polyphyletic. For instance, the phylogenetic analysis of Wible et al. (2007) included two "palaeoryctids", Cimolestes and Eoryctes (Eoryctes is more likely to represent the Palaeoryctidae proper), and while Cimolestes appeared outside the placental crown group, Eoryctes was placed among the insectivorans as the sister to Potamogale (Tenrecidae). If creodonts (either or both families) are closer to Cimolestes, they may be stem-eutherians. If they are closer to Palaeoryctidae proper, they may even be afrotheres (Wible et al. did not support placement of tenrecs among afrotheres, but it is notable that the earliest hyaenodontids are African). Placement of either the Oxyaenidae or the Hyaenodontidae still awaits proper analysis.CKT090807

Notes

[1] This does not necessarily mean that he thought they were specifically related to modern insectivorans such as shrews and hedgehogs. Cope and most of his contemporaries would have regarded the "Insectivora" as representing the generalised basal form from which all other placental mammals were derived, and recent insectivorans would have been the remnants of that original grade.

[2] It is also notable that Cope regarded the aye-aye as forming a separate suborder from other prosimians, due to its rodent-like incisors. Cope (1884) held that the tillodonts were "intimately allied to the living Chiromys [aye-aye] of Madagascar, which is itself almost a lemur, by general consent" (emphasis mine).

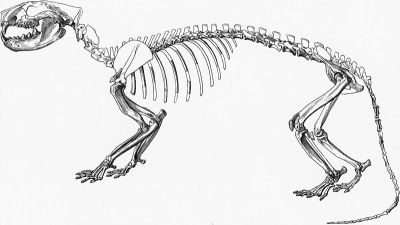

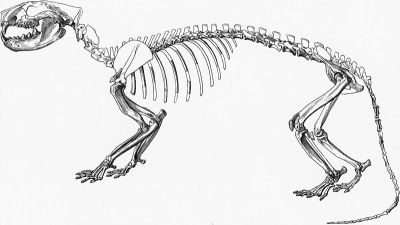

Descriptions

Oxyaenidae: Machaeroides, Oxyaena, Palaeonictis, Patriofelis, Sarkastodon

Range: Paleocene to Eocene of North America, Europe, and Asia

Phylogeny: Placentalia/Crown Group Placentalia ::: *

Comments: Once considered ancestral to felids, the Oxyaenids are now considered to be an unrelated group of early carnivores. Despite being included with the Hyaenodonts in the Creodontia, very little unites the two groups. Oxyaenids had a short, broad skull, deep jaws, and teeth designed for crushing rather than shearing. These animals seem to have been able to climb trees. - adapted from Wikipedia MAK120716

Image: Oxyaena lupina, Early Eocene of North America, public domain, via Wikipedia

Hyaenodontidae: Hyaenodon, Megistotherium, Pterodon, Sinopa

Range: Late Paleocene to Late Miocene of Africa, Europe, Asia and North America

Phylogeny: Placentalia/Crown Group Placentalia or Afrotheria, ::: *

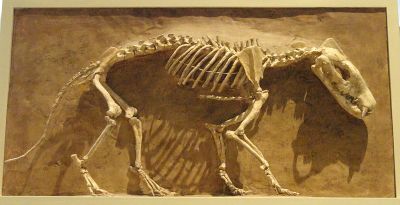

Comments: the most successful and abundant of the mid Tertiary predators. They were vaguely dog-like in appearance (another way of saying "generalised cursorial mammalian carnivore") and walke don their toes (digitigrade) rather than bear-like on the flat foot as most other early mammals did. The skull was long and the molars were scissor-like (adapted for shearing), indicating a hypercarnivorous diet (flesh only like a felid, rather than being an omniovore). Although most species were dog sized, a few grew larger. Hyaenodon horridus (right) is the common North American species, and was about the size of a wolf. The Asian species H. gigas and H. weilini were much larger, while the early Miocene Megistotherium osteothlastes of Northern Africa reached the maximum size for a terretsrial mammalian preditor, exceeding half a tonne in weight and could have easily taken down rhinos and immature mastodons (why no terrestrial mammalian carnivores equalled allosaurs, charcharodontosaurs, or tyrannosaurs in size is not clear).

Image: Hyaenodon horridus, Niobrara County, Wyoming, USA, Late Oligocene. Exhibit in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Photo by Daderot, public domain, via Wikipedia

Links: Wikipedia MAK120716