Gruimorpha: Overview

Introduction

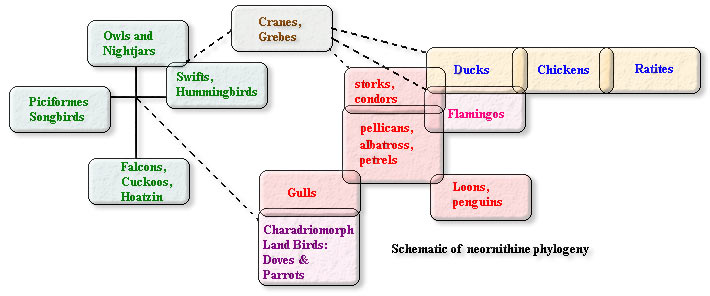

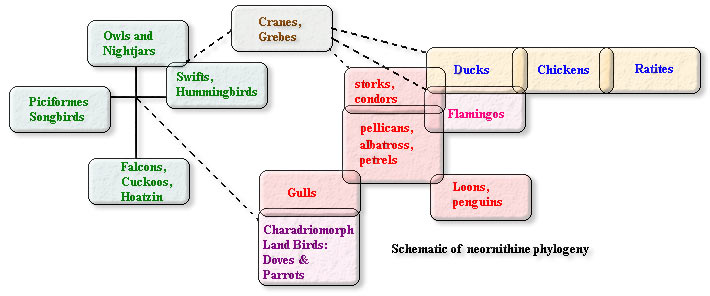

As always, it is nearly impossible to say anything sensible about bird phylogenies. Most phylogenies include at least two of the following as close relationships: ratites and galliforms, galliforms and ducks, ducks and flamingos, flamingos and storks, ducks and storks, storks and the pelican/penguin group, flamingos and/or storks and the gull/dove/parrot group. Based on this vague, but vaguely consistent findings, we have supposed that these groups are more closely related to each other than they are to everyone else. Specifically, we have placed them all in an expanded Galloanserae, with the hope that they will eventually sort themselves out.

As always, it is nearly impossible to say anything sensible about bird phylogenies. Most phylogenies include at least two of the following as close relationships: ratites and galliforms, galliforms and ducks, ducks and flamingos, flamingos and storks, ducks and storks, storks and the pelican/penguin group, flamingos and/or storks and the gull/dove/parrot group. Based on this vague, but vaguely consistent findings, we have supposed that these groups are more closely related to each other than they are to everyone else. Specifically, we have placed them all in an expanded Galloanserae, with the hope that they will eventually sort themselves out.

The flamingos and some of their charadriomorph relatives, as well as the ducks, are also associated on occasion with the cranes and grebes. However, this association lacks even the vaguely linear pattern of the pairwise associations listed above. We have placed them, therefore, at the root of the Gruimorpha, a separate radiation of neornithines into which we have thrown everything else in the manner of a child who throws all of his belongings under the bed to avoid the burden of placing them in some more rational and orderly arrangement. This set includes the owls and nightjars, which may have a close relationship to the swifts and hummingbirds. Falcons and cuckoos form a third segment of the gruimorphs; and, finally, the Piciformes and passerine birds are usually grouped together as a fourth segment. Truthfully, there is little to relate the cranes and grebes with the rest of the taxa we have included in the Gruimorpha, so we have shown the relationship as very tentative.

The gruimorph group (minus the cranes and grebes) actually does have some common features, although not of the sort that typically make their way into cladograms. First, none of these bird orders has any Mesozoic fossil record. Hope (2002). Second, they are all land birds. In addition to being interesting, this is also suspicious. The fossil record of birds is notoriously poor, as their hollow bones don't keep well. Absence from the fossil record is never a strong signal, and land birds are even less likely to be fossilized than shore birds. Second, any anatomical characters they share may relate to the loss of typically aquatic adaptations. Third, the charadriomorphs have their own small set of land birds in the dove and parrot group.

It is on this last point that many bird phylogenies come to grief -- or at least come to disagree. The internal logic of the land bird assemblage is fairly good. While not compelling, there is nothing in the arrangement which immediately raises eyebrows. However, once the doves and parrots are permitted to associate with the other land birds, the internal structure of the land bird assemblage falls apart. Phylogenies which join all land birds together -- and the current lot of cladograms in the literature almost all recover such a relationship -- spread the land bird taxa out in a distressingly inconsistent number of ways. In fact, there is a strong tendency to break up some moderately well-established avian orders.

We strongly suspect that this result is correct. We have not yet rearranged our bird sections on this model only because there is not yet enough consistency between cladograms to tell us what the new order of land bird taxa might look like -- and of course it would be a hell of a lot of work ... . Thus Sloth and Caution both counsel delaying another year or two before we embark on this path, and who are we to argue with such counselors?

ATW040826 Public domain. No rights reserved.

As always, it is nearly impossible to say anything sensible about bird phylogenies. Most phylogenies include at least two of the following as close relationships: ratites and galliforms, galliforms and ducks, ducks and flamingos, flamingos and storks, ducks and storks, storks and the pelican/penguin group, flamingos and/or storks and the gull/dove/parrot group. Based on this vague, but vaguely consistent findings, we have supposed that these groups are more closely related to each other than they are to everyone else. Specifically, we have placed them all in an expanded Galloanserae, with the hope that they will eventually sort themselves out.

As always, it is nearly impossible to say anything sensible about bird phylogenies. Most phylogenies include at least two of the following as close relationships: ratites and galliforms, galliforms and ducks, ducks and flamingos, flamingos and storks, ducks and storks, storks and the pelican/penguin group, flamingos and/or storks and the gull/dove/parrot group. Based on this vague, but vaguely consistent findings, we have supposed that these groups are more closely related to each other than they are to everyone else. Specifically, we have placed them all in an expanded Galloanserae, with the hope that they will eventually sort themselves out.