The mandible of Khoratpithecus piriyai from Chaimanee et al. (2004).. Scale bar equals 1 cm.

| Primates | ||

| The Vertebrates | Ponginae |

| Vertebrates Home | Vertebrate | Vertebrate |

|

Abbreviated Dendrogram

Archonta

│

└─Primates

├─Strepsirhini

└─Haplorhini

├─Tarsiiformes

└─Anthropoidea

├─Platyrrhini

└─Hominoidea

├─Hylobatidae

└─Hominidae

├─Ponginae

│ ├─Sivapithecus

│ ├─Gigantopithecus

│ └─Pongo

└─Homininae

├─Gorilla

└─┬─Samburupithecus

└─┬─Pan

└─Hominini

|

Contents

Overview |

Taxa on This Page

|

The mandible of Khoratpithecus piriyai from Chaimanee et al. (2004).. Scale bar equals 1 cm. |

The subject of today's Taxon of the Week post is the Ponginae. Rather than comment directly on the prolonged, bitter and largely pointless arguments on ape beta taxonomy, I'll simply note that for this post I'm restricting Ponginae to the clade including the modern orangutans and fossil apes closer to orangs than other modern apes.

I say 'orangutans' because there are two distinct modern varieties that are listed as separate species by Groves (2005), the Sumatran Pongo abelii and the Bornean P. pygmaeus. During the Pleistocene, orangutans were also found in continental south-east Asia and southern China (Bacon & Long 2002). Previous to the Pleistocene, however, a gap of six or seven million years separates Pongo from their generally accepted relatives in the Miocene genera Sivapithecus and Khoratpithecus (Finarelli & Clyde 2004; Chaimanee et al. 2004). Other possible pongine genera whose position is less firm include Lufengpithecus, Ankarapithecus and Gigantopithecus. In the phylogenetic analysis by Finarelli & Clyde (2004), the Miocene Lufengpithecus and Ankarapithecus were initially placed on the orangutan stem on the basis of morphology, but switched over to the base of the stem of the African ape-human clade under an analytical method that attempted to reduce stratigraphic incongruence.

Sumatran orangutan Pongo abelii drinking while neatly concealing her baby. Photo from here.. |

Sivapithecus is the best-known of the fossil pongines, with a number of species assigned to it from India dating from about 12.8 to 7.4 million years ago. Though Sivapithecus was similar to modern orangutans in skull morphology, it differed in its dentition and postcranial morphology. Sivapithecus lacked the adaptations for brachiation of orangutans; when moving in trees, it would have run along the top of branches in the manner of a monkey rather than swinging underneath the branches like an orangutan. Arm-swinging was probably a later innovation on the orangutan line (and would have therefore developed independently from other arm-swingers such as gibbons). Khoratpithecus, currently known only from teeth and jaw bones, had dentition more similar to Pongo and is probably more closely related to modern orangs than Sivapithecus; unfortunately, we do not yet know whether it retained the plesiomorphic postcranial morphology of Sivapithecus.

Skull of Sivapithecus indicus. Photo by FunkMonk. |

Ankarapithecus is a smaller ape that, as its name suggests, was found in Turkey. If it is a pongine, it would increase the known range for that clade. An even greater range has been suggested by the assignation of the Spanish Hispanopithecus to the pongine line (Cameron 1997), though it was instead assigned to a non-pongine clade of European apes by Begun (2009). As indicated above, Ankarapithecus and the Chinese Lufengpithecus show features that could be interpreted as showing relationships to either pongines or hominines. Indeed, some fossils now regarded as Lufengpithecus were initially assigned to Homo (Harrison 2002), though possibly that may say more about the expectations of Chinese palaeoanthropology than about Lufengpithecus itself.

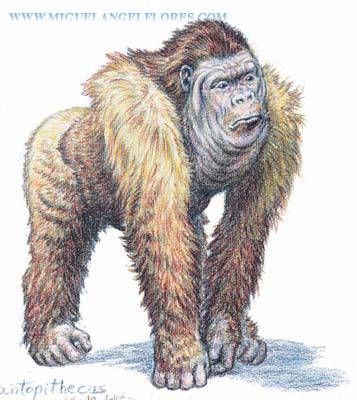

Reconstruction of Gigantopithecus troop. Image from here. |

The only potential pongine other than Pongo itself known from later than the Miocene is Gigantopithecus. Three species have been assigned to this genus: the Pleistocene Gigantopithecus blacki from China and two Miocene species from Indo-Pakistan (the Indo-Pakistan species were smaller than G. blacki, but still larger than most other apes). A significant time gap separates the Chinese and Indo-Pakistani species, and it has been suggested that they may represent two separate lineages that independently attained large size (in which case the Indo-Pakistani species are placed in the genus Indopithecus). Gigantopithecus blacki had the largest teeth of any known ape, but without any post-cranial remains it is difficult to know its overall size. Johnson (1979), assuming the proportions of Gigantopithecus blacki to be similar to those of a modern gorilla, suggested that it may have weighed around 270 kg (vs about 160 kg for a gorilla) with long bones about 20% longer than those of a gorilla. However, it has been suggested that the large teeth of Gigantopithecus were specialised for feeding on bamboo (Kupczik & Dean 2008), in which case it may have had larger teeth relative to body size than other apes (it is notable in this light that the incisors of Gigantopithecus were actually smaller than a modern great ape's: Woo 1962). At any case, estimates that Gigantopithecus was more than twice the size of a modern gorilla seem unlikely. CKT110106

Ponginae South and East Asian great apes; Old Men of the Woods > Old Men

Range: From the Miocene of Southern and Eastern Asia

Phylogeny: Hominidae : Dryopithecus + (Pierolapithecus + (Homininae + * : Sivapithecus + Gigantopithecus + Pongo))

Sivapithecus : S. indicus, S. sivalensis, S. parvada

Synonym: Ramapithecus

Range: Miocene of theSiwalik Hills and Pothowar plateau of India, Nepal, and Pakistan

Phylogeny: Ponginae : Gigantopithecus + Pongo + *

Comments: About the size of a modern orangutan or chimpanzee. The shape of its wrists and general body proportions suggest that it may have spent a significant amount of its time on the ground. It had large canine teeth, and heavy molars, suggesting a diet of relatively tough food, such as seeds and savannah grasses,, although fruit would also be part of the diet. The most recently discovered species, S. parvada, is also the largest . - from Wikipedia

Ramapithecus was at one time considered a hominid ancestor but is now understood to be a synonym of (and possibly the female of) Sivapithecus. One species, R. punjabicus, has been reassigned to Dryopithecus MAK120710

Gigantopithecus : G. bilaspurensis, G. blacki, G. giganteus

Range: Miocene to Pleistocene of South and East Asia (India, China, and Vietnam)

Phylogeny: Hominidae : Sivapithecus + Pongo + *

Characters: jaws are deep and very thick. The molars are low crowned and flat and exhibit heavy enamel suitable for tough grinding. (Olejniczaketal2008) The premolars are broad and flat and configured similarly to the molars. The canine teeth are neither pointed nor sharp, while the incisors are small, peglike and closely aligned. The features of teeth and jaws suggested that the animal was adapted to chewing tough, fibrous food by cutting, crushing and grinding it. Gigantopithecus teeth also have a large number of cavities, similar to those found in giant pandas, whose diet, which includes a large amount of bamboo, may be similar to that of Gigantopithecus. (Coichon 1991) - from Wikipedia

Comments: Contemporary with early humans. Relatively few fossils are known; most of the material are molars from Chinese traditional medicine shops, although several jawbones are known. The largest species, Gigantopithecus blacki is the largest known primate. However estimates heights of upto 3 metres and weight to 540 kilograms are probably exagerrations. The species was highly sexually dimorphic, with adult females roughly half the weight of males. It probably inhabited bamboo forests, since its fossils are often found alongside those of extinct ancestors of the panda. Most evidence points to Gigantopithecus being a plant-eater.

At one time Gigantopithecus was thought to have been related of humans, on the basis of similar morphology of the molars; this has turned out to be a result of convergent evolution.

Gigantopithecus seems to have consumed a variety of vegetable foods, as suggested by the analysis of the phytoliths adhering to its teeth. An examination of the microscopic scratches and gritty plant remains embedded in Gigantopithecus teeth suggests that they ingested seeds and fruit as well as bamboo. (Poirier & McKee 1999) - from Wikipedia MAK120710

Graphics: Gigantopithecus life reconstruction by Miguel Angel Flores, Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike. Fossil jaw of Gigantopithecus blacki, Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano. Photo by Ghedoghedo Wikipedia,GNU Free Documentation/Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike

Range: Recent of South-East Asia (Borneo and Sumatra)

Phylogeny: Hominidae : Sivapithecus + Gigantopithecus + *

Comments: South-East Asian, highly arboreal, solitary species. Highly intelligent, tools-using (for procrurtng insecst aor fruit), build elaborate sleeping nests, may even be distinctive cultures within populations. Field studies of the apes were pioneered by primatologist Birute Galdikas. Two species (originally subspecies), P. pygmaeus (Borneo) and P. abelii (Sumatran) which according to molecular dating diverged around 400,000 years ago. Both species are Endangered with the Sumatran orangutan being Critically Endangered, due to poaching, habitat destruction and the illegal pet trade. There are several conservation and rehabilitation organisations dedicated to the survival of orangutans in the wild. - from Wikipedia MAK120710

Graphic: Sumatran Orangutan (Pongo abelii), photo by cykocurt Creative Commons, copied from Animal Cognition blog

page MAK120710, essay by Christopher Taylor, Catlogue of Organisms at 1/06/2011 11:52:00 AM