| Palaeos |  |

Archosauria |

| Vertebrates | Ornithosuchus |

| Page Back | Unit Home | Unit Dendrogram | Unit References | Taxon Index | Page Next |

| Unit Back | Vertebrates Home | Vertebrate Dendrograms | Vertebrate References | Glossary | Unit Next |

|

Abbreviated Dendrogram

ARCHOSAUROMORPHA | `--ARCHOSAURIA |--Proterosuchidae `--+--Erythrosuchidae `--+--Euparkeriidae `--Crown Group Archosauria |--Ornithodira | |--PTEROSAURIA | `--DINOSAUROMORPHA `--Crurotarsi |--Phytosauridae `--Rauisuchiformes |--Rauisuchia | |--Ornithosuchidae | | |--Ornithosuchus | | |--Venaticosuchus | | `--Riojasuchus | `--+--Prestosuchidae | `--Rauisuchidae `--Suchia |--Aetosauridae `--CROCODYLOMORPHA |

Contents

Overview |

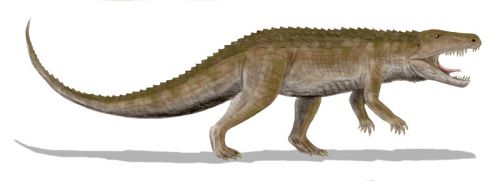

Life reconstruction of Ornithosuchus longidens Artwork by Nobu Tamura , via Wikipedia, GNU Free Documentation/Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike |

The

Carnian Carnosaurs of Moray Firth

The

Carnian Carnosaurs of Moray FirthIn these latter days of dinosaur paleontology, most of the main lines of descent in that part of phylospace have been sketched out. We tend to dismiss papers like Walker (1964) as hopelessly obsolete. Walker argued that Ornithosuchus was ancestral to the "megalosaurs" and carnosaurs of the Jurassic. Now, it is fair to say that he was quite wrong, and that he was misled by similar characteristics which Carnosauria and ornithosuchians evolved independently. However, it would be a mistake to suppose that Walker was foolish or unobservant. The similarities, as we will see, are rather startling. But, more to the point, it would be an even more serious mistake to disregard Walker's wrong ideas about phylogeny as useless antiques.

Synapomorphies -- unique characteristics -- are the keys to phylogeny. Synapomorphies tell who is related to whom. But homoplasies -- "convergent" characteristics -- are the keys to evolution. Homoplasies might tell us why animals evolved as they did. If two closely related animals are alike, we learn nothing except that they are related. If two unrelated animals are alike, we can legitimately suspect that they were subject to similar selective pressures. By sorting out the characters they do share from the characters they don't share, we may be able to determine what selective pressures were most important in shaping the forms we observe in the fossil record.

The wrong ideas about phylogeny in prior decades are thus potentially much more useful than right ideas. No one today needs to know why Walker thought Hallopus was a crocodylomorph. Walker (1970). He was entirely correct; but we have better fossils now, as well as some improved analytical tools; and these can usually be counted on to give us better reasons than Walker had. On the other hand, erroneous phylogenies by experienced and competent observers like Alick Walker are pre-compiled collections of homoplasies ripe for analysis of selective pressures. This data is much harder to collect today, since compiling this kind of information requires that we put aside what we have learned so laboriously in working out the correct phylogeny.

Some of the homoplasies involved are really extraordinary. By way of example, we show the skull of the ornithosuchid Ornithosuchus on the right from the Carnian (Late Triassic) of Scotland [1], adapted from Walker (1964). On the left is the allosauroid Sinraptor, from the Late Jurassic of China, as reconstructed by Currie & Zhao (1993). Their last common ancestor was probably something like Euparkeria from the Middle Triassic of South Africa.

Thus,

eighty million years and tens of thousands of miles separate Sinraptor

from its last common ancestor with Ornithosuchus. Yet the two share

numerous details of skull structure. The nares are enlarged and bordered

almost entirely by the premaxilla. The nares are extended by a

well-developed posterodorsal fossa. The anterior margin of the antorbital

fenestra is strongly developed as an elaborate, rimmed fossa comprised of an

ascending maxillary process. The maxilla and lacrimal meet on the dorsal

rim of this fenestra in a tight, complex suture. The skull table is long

and narrow. It contains a probable transverse hinge (albeit very

differently placed and formed). A transverse ridge marks the posterior end

of the skull table, and the upper temporal fenestrae are deeply inset and

sharply marked off. The lacrimal and jugal form the antorbital bar.

The bar is twisted, with part of the upper surface rugose. The orbit is

triangular with markedly roughened surfaces dorsal to the midline of the

orbit. The postorbital has a rugose lateral projection above the

orbit. The maxilla meets the jugal below the orbit. In Ornithosuchus,

the maxilla forks and grasps the jugal with multiple tines. In Sinraptor

the junction is simple, but the jugal - quadratojugal suture is split.

The lower temporal fenestra is large, and the squamosal and quadratojugal meet

behind it at an angle. The dentary is more massive anteriorly in Ornithosuchus,

in almost every other respect the jaws virtually identical, with the same bones

covering essentially the same areas around an enlarged mandibular fenestra,

bearing the same large posterior fossa. Both have a short, fairly strong

retroarticular process. The tooth row is rather short and ends about level

with the preorbital bar.

Thus,

eighty million years and tens of thousands of miles separate Sinraptor

from its last common ancestor with Ornithosuchus. Yet the two share

numerous details of skull structure. The nares are enlarged and bordered

almost entirely by the premaxilla. The nares are extended by a

well-developed posterodorsal fossa. The anterior margin of the antorbital

fenestra is strongly developed as an elaborate, rimmed fossa comprised of an

ascending maxillary process. The maxilla and lacrimal meet on the dorsal

rim of this fenestra in a tight, complex suture. The skull table is long

and narrow. It contains a probable transverse hinge (albeit very

differently placed and formed). A transverse ridge marks the posterior end

of the skull table, and the upper temporal fenestrae are deeply inset and

sharply marked off. The lacrimal and jugal form the antorbital bar.

The bar is twisted, with part of the upper surface rugose. The orbit is

triangular with markedly roughened surfaces dorsal to the midline of the

orbit. The postorbital has a rugose lateral projection above the

orbit. The maxilla meets the jugal below the orbit. In Ornithosuchus,

the maxilla forks and grasps the jugal with multiple tines. In Sinraptor

the junction is simple, but the jugal - quadratojugal suture is split.

The lower temporal fenestra is large, and the squamosal and quadratojugal meet

behind it at an angle. The dentary is more massive anteriorly in Ornithosuchus,

in almost every other respect the jaws virtually identical, with the same bones

covering essentially the same areas around an enlarged mandibular fenestra,

bearing the same large posterior fossa. Both have a short, fairly strong

retroarticular process. The tooth row is rather short and ends about level

with the preorbital bar.

These are, obviously, not small matters. In particular, the similarity of the structures surrounding the antorbital fenestra is downright odd. In some imaginative dinosaur reconstructions, this is often an area with a colorful, inflated area of skin used as a mating display, as it is in some lizards today. In other reconstructions, the region is simply patched over since the structure has no obvious purpose. Yet, this extraordinary similarity suggests that it may have been strictly functional, an organ or structure so highly constrained by its purpose that it appears in almost precisely the same form in two lineages with no direct relationship. The similarities in the orbital region, immediately posterior, are not quite so uncanny at first sight. However, in some ways they are even weirder, since the skull tables of Ornithosuchus and Sinraptor are put together quite differently. What possible use is the little pocket and lacrimal awning above the antorbital fenestra? Why is the preorbital bar twisted and dorsally rugose? Did they have eyestalks like snails? It hardly seems likely. What does seem likely is that these peculiar similarities are likely the only remaining evidence of important selective factors that shaped large terrestrial carnivores consistently over an enormous period of time in the early Mesozoic and beyond.

[1] In fact, on the south shore of Moray Firth -- hence the name of our essay.

ATW040130.

Ornithosuchus: Newton

1894. O. longidens (Huxley 1877)

Ornithosuchus: Newton

1894. O. longidens (Huxley 1877)

Range: Late Triassic (Latest Carnian) of Scotland

Phylogeny: Ornithosuchidae : Venaticosuchus + Riojasuchus + *.

Characters: length to 4 m, skull to 45 cm [W64]; premaxilla recessed posteriorly for passage of enlarged

dentary teeth [W64] [3]; skull table slopes smoothly up to frontals

[W64]; nasal with strong medial flange posterior to nares, supported by ascending

process of maxilla [W64]; continuous suture between nasal + frontal and lacrimal

+ prefrontal + postfrontal [W64] [1]; postfrontal confined to skull table

[W64]; skull table posterior to frontals slightly raised [W64]; postorbitals

& parietals form most of UTF [W64]; parietals with occipital flanges [W64] [2];

maxilla excluded from naris by premaxilla - nasal suture [S91]; maxilla overlies lacrimal with a thin squamous

suture and also bears thin process inserting between lacrimal &

nasal [W64]; maxilla forks posteriorly, where it meets the jugal [W64] [$S91]; lacrimal

with strongly rugose,

posteriorly - directed flange on descending process [W64]; jugal, lacrimal

process tapers to a point, fitting into a groove in the descending process of

the lacrimal [W64]; opposite articulation with postorbital (i.e., groove on the

jugal) [W64]; maxilla and jugal with strong lateral ridge [W64] [4];

postorbital dorsally rugose, with strong crest overhanging its own descending process

[W64] [$S91]; squamosal - quadratojugal bar with strong anterior projection [W64];

external surface of quadratojugal strongly rugose [W64]; quadrate with small,

thin, triangular process extending onto surface of pterygoid [W64]; large

quadrate foramen [W64]; occipital area poorly known [W64]; probably a large,

rectangular supraoccipital [W64]; laterosphenoid present [S91]; anterior palate [5] not well known

& median contact of maxillae is not certain [W64]; palatines arch strongly

upwards, forming a vault with the anterior processes of the pterygoids [W64];

pterygoids with long, straight, rod-like anterior bars, meeting antimere

along a flat medial surface [W64]; small anterodorsal pterygoid processes may

have defined notch for cartilaginous epipterygoid [W64]; pterygoids with short,

blunt, ventrally directed transverse

flange [W64]; basipterygoid

process small, located between parabasal

process and quadrate

ramus [W64]; dentary symphysis long [W64]; anterior dentary curves

medially to form symphysis & accommodate anterior maxillary teeth [W64];

splenials medially flat & meet in short splenial symphysis [W64]; angular

with long anterior process passing into jaw and between dentary & splenial,

forming floor of Meckelian

canal [W64]; angular forming concave lower margin of posterior jaw [$S91]

[7]; surangular large, forming much of mandibular fenestra, with

marked rugosity posterodorsally [W64]; surangular with foramen near

ventral margin, under jaw articulation [$S91]; small coronoid present [W64];

prearticular small, probably with some lateral exposure and short retroarticular

process [W64]; articular blocky and complex, with articular surface

facing ?medially [W64]; interdental plates alternate with teeth [W64]; teeth

laterally compressed, more rounded anteriorly than posteriorly, recurved and

finely serrated on posterior & distal anterior edges [W64]; premaxilla with

3 teeth, with 1st or 2nd largest [W64]; <10 maxillary teeth & ~10 dentary

teeth [W64]; dentary with small, anterior, procumbent tooth [S91]; neural canal large & "sag" down into centra [W64]; 24

presacral vertebrae, with no clear cervical - dorsal distinction & all of

about the same length [W64]; 3 sacrals (plus one partially incorporated) & 45-50 caudals [W64]; cervical

centra strongly compressed between articular ends, especially ventrally [5] [W64];

dorsals constricted, but without ventral keel [W64]; parapophyses

start low on centrum & move up onto arch, diapophyses

begin low on arch, directed ventrally and move dorsally, oriented more

laterally, along the dorsal series [W64]; both parapophyses & diapophyses

with various supporting ridges, particularly to zygapophyses

[W64]; cervicals with narrow neural spines, with transversely expanded apices

(compare Euscolosuchus) [W64];

ribs short, slender & poorly known [W64]; caudal centra become round &

spool-like, ventrally grooved from 3rd caudal & with broadly expanded

transverse processes [W64]; proximal caudal neural spines much taller than any

others [W64]; caudal centra with anterior vertical median lamina

[W64]; clavicle present , interclavicle long & very thin [W64]; scapula

slender, with gradual distal expansion [W64] [6]; small, oval muscle

attachment area above glenoid [W64]; scapulocoracoid

notch minor or absent [W64]; coracoid thin and crescent-shaped, pointed

posteriorly, forming

most of large, shallow glenoid

[W64]; forelimb <2/3 length of hindlimb [W64]; major limb bones probably

hollow [W64]; humerus very thin with large deltopectoral

crest, small internal

tuberosity & deep anterior trochlear recess [W64]; radius very

slender with lateral recess distally overlapped by an ulnar shelf [W64]; ulna

somewhat stouter, with poorly developed olecranon [W64]; distal ulna curves

postaxially (very unusual) [W64]; probably 5 digits on manus, I largest and rest

progressively smaller [W64]; manus I may

have been opposable (!?) [W64]; ilium  tall, peaking above anterior part of

acetabulum, curving ventrally & laterally posterior to acetabulum [W64];

ilium with marked medial shelf for sacral ribs [W64]; acetabulum deep, perforate

in part, with strong supraacetabular

shelf [W64]; pubis with large pubic foramen and long, continuous pubic

symphysis, with a sort of bifid pubic boot [W64]; ischium with obturator

process interrupting symphysis (medial edges bent anteroventrally to

form obturator process) [W64]; femoral head with distinct medial bend, but

without well-defined neck [W64]; greater

trochanter small, probably finished in cartilage, but lesser

trochanter well developed [W64]; 4th

trochanter present as elongate ridge on medial face of femur [W64];

femoral shaft with slight anteriorly - directed bow [W64]; tibia with triangular

proximal face & well-developed laterally-curving cnemial

crest [W64]; crus shorter than femur [W64]; calcaneum with prominent

tuber & calcaneal form suggests croc-reversed tarsus, but region is not

well-preserved in any specimen [W64]; pes digits symmetrical about III, with

none greatly reduced [W64]; skull with irregular ornament of small pits [W64];

paired paramedian scutes sutured across the midline arranged so as to cap neural

spines [W64]; caudal scutes fuse

across midline after 10th caudal [W64].

tall, peaking above anterior part of

acetabulum, curving ventrally & laterally posterior to acetabulum [W64];

ilium with marked medial shelf for sacral ribs [W64]; acetabulum deep, perforate

in part, with strong supraacetabular

shelf [W64]; pubis with large pubic foramen and long, continuous pubic

symphysis, with a sort of bifid pubic boot [W64]; ischium with obturator

process interrupting symphysis (medial edges bent anteroventrally to

form obturator process) [W64]; femoral head with distinct medial bend, but

without well-defined neck [W64]; greater

trochanter small, probably finished in cartilage, but lesser

trochanter well developed [W64]; 4th

trochanter present as elongate ridge on medial face of femur [W64];

femoral shaft with slight anteriorly - directed bow [W64]; tibia with triangular

proximal face & well-developed laterally-curving cnemial

crest [W64]; crus shorter than femur [W64]; calcaneum with prominent

tuber & calcaneal form suggests croc-reversed tarsus, but region is not

well-preserved in any specimen [W64]; pes digits symmetrical about III, with

none greatly reduced [W64]; skull with irregular ornament of small pits [W64];

paired paramedian scutes sutured across the midline arranged so as to cap neural

spines [W64]; caudal scutes fuse

across midline after 10th caudal [W64].

Notes: [1] Walker does not mention it, but note that the naso-frontal suture is also continued by the lacrimal - prefrontal suture. It is difficult to explain this unless the skull were highly kinetic in this region. [2] Walker speculates that these supported the most anterior set of armor plates [W64]. [3] Is it also for a sliding joint with the maxilla? [4] Note the similarity to Erpetosuchus and probably also poposaurs. [5] c.f. Saurosuchus. [6] The general form of the post-cranial skeleton is illustrated at Ornithosuchidae. [7] however this is also perhaps true of Postosuchus.

Comments: Known from skull and postcrania, Ornithosuchus was the first member of this family to be described, from the late Carnian Lossiemouth Beds of Elgin, Scotland. At 3.3 metres or more in length, this was a large animal, without doubt the top predator of its environment. Originally reconstructed as a biped, and certainly capable of bipedal locomotion, it probably spent most of its time on all fours. The skull is strikingly similar to that of large theropod dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus, leading to the suggestion at one time that tyrannosaurs originally evolved directly from ornithosuchids (this is now not believed to be the case). Although at one time believed to be a primitive member of the Dinosauria, Ornithosuchus, like other members of its family, have a number of primitive (plesiomorphic) features, such as a double row of bony plates down its back, a short broad pelvis attached to the backbone by only 3 vertebrae, and five toes on each hind foot (as opposed to three in the case of theropod dinosaurs). These characteristics are shared by most basal archosauromorphs, and show that Ornithosuchus is only distantly related to the dinosaurs. MAK.References: Sereno (1991) [S91], Walker (1964) [W64]. MAK030730, ATW031130.

| Page Back | Unit Home | Page Top | Page Next |

checked ATW040109

Using this material. All material by ATW is public domain and may be freely used in any way (also any material jointly written by ATW and MAK). All material by MAK is licensed Creative Commons Attribution License Version 3.0, and may be freely used provided acknowedgement is given. All Wikipedia material is either Gnu Open Source or Creative Commons (see original Wikipedia page for details). Other graphics are copyright their respective owners