of Deep Time

| Palæos: |  |

Historical discovery of Deep Time |

| Time | Geology and the discovery of Deep Time |

|

Timescale Main Page

The Discovery of Deep Time Premodern concepts of Time Geology and the discovery of Deep Time - Reading List |

Deep time, geology, and paleontology Links |

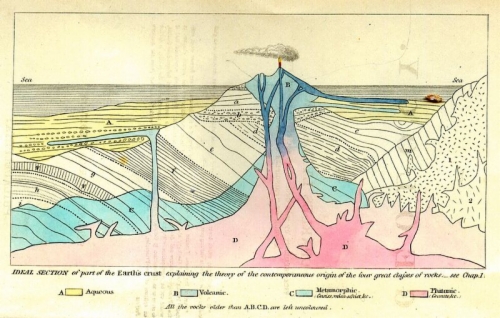

Frontispiece to Lyell's Principles of Geology (public domain); from Book Drum |

Deep time, geology, and paleontology: The following continues with Wikipedia:

In classical antiquity, Aristotle saw that fossil seashells from rocks were similar to those found on the beach and inferred that the fossils were once part of living animals. He reasoned that the positions of land and sea had changed over long periods of time. The 11th-century Persian geologist Avicenna (Ibn Sina) examined various fossils and inferred that they originated from the petrifaction of plants and animals. He also first proposed one of the principles underlying geologic time scales: the law of superposition of strata. Later in the 11th century, the Chinese naturalist, Shen Kuo, also recognized the concept of 'deep time'. Leonardo da Vinci like Aristotle, considered that fossils were the remains of ancient life.

Following the Protestant Reformation, the Genesis creation stories were interpreted as holding that the Earth has existed for only a few thousand years (this is still the position of Young Earth creationism today). Proponents of scientific theories which contradicted scriptural interpretations could not only lose their academic appointments but were legally answerable to charges of heresy and/or blasphemy, charges which, even as late as the 18th century in Great Britain, sometimes resulted in a death sentence.

Early geologists such as Nicolas Steno and Horace-Bénédict de Saussure developed ideas of geological strata forming from water through chemical processes. In the late 17th century. Steno argued that rock layers (or strata) are laid down in succession, and formulated the law of superposition, which states that any given stratum is probably older than those above it and younger than those below it. These insights constituted the foundation of the science of geology

Abraham Gottlob Werner developed into a theory known as Neptunism. The Neptunists, as their name indicates, believed the continents formed through deposition from a vast, primordial super-ocean. It was thought that as this ocean withdrew in stages, successive rock formations were deposited. First came the Primitive or Primary rocks, then the Secondary, than finally the Alluvial or Tertiary. Werner thus was the first to give periods and eras names, of which the Tertiary is still used today.

Neptunism was soon suplanted by Plutonism, the belief that the rocks and continents came about through the outwelling of volcanic material (larva, which hardened into volcanic (igneus) rock). This theory, initiated by the great Scottish geologist James Hutton, who described gradual geological processes operating continuously over deep time, and represented the beginning of modern geology. Hutton's innovative 1785 theory based on visualised an endless process of rocks forming under the sea, being uplifted and tilted, then eroded to form new strata under the sea. In 1788 the sight of Hutton's Unconformity at Siccar Point convinced Playfair and Hall of this extremely slow cycle, and in that same year Hutton memorably wrote "we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end".

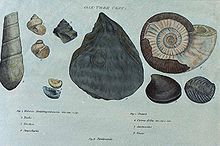

A plate from William Smith's 1816 work Strata Identified by Organized Fossils (Wikipedia (Public domain)) |

In 1796, Georges Cuvier published his findings on the differences between living elephants and those known from fossils. his analysis identified mammoths and mastodons as distinct species, different from any living animal, and effectively ended a long-running debate over whether the extinction of a species was possible. In the 1790s William Smith began the process of ordering rock strata by examining fossils in the layers while he worked on his geologic map of England. Independently, in 1811, Georges Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart published an influential study of the geologic history of the region around Paris, based on the stratigraphic succession of rock layers.

The identification of strata by the fossils (a method still used today, and known as biostratigraphy) enabled geologists to divide Earth history more precisely. It also enabled them to correlate strata across national (or even continental) boundaries. If two strata (however distant in space or different in composition) contained the same fossils, chances were good that they had been laid down at the same time. This research helped establish the antiquity of the Earth. Cuvier advocated catastrophism to explain the patterns of extinction and faunal succession revealed by the fossil record.

Diagram of the geologic timescale from an 1861 book by Richard Owen showing the appearance of major animal types (Wikipedia; Public Domain). European geological strata are shown on the left, geological periods and epochs in the middle, and various forms of life on the right. This is essentially the same presentation as we know today, and represents the beginning of a comprehensive account of the history of the Earth and the story of the rise and fall of various dynasties of life, hence the sequence invertebrates, fish (Paleozoic), reptiles (Mesozoic), and birds and mammals (Cenozoic). This replaced biblical theology and six days of creation with a new "creation story", a new cosmological account of the history of the world and the universe. Universal History, the story of humanity, then becomes only a small epoch right at the top. The only thing still missing is an understanding of evolution; the transformation of species, but that came soon |

As knowledge progressed, the need arose to formulate a systematic classification of rock strata. Two English geologists, ![]() Adam Sedgwick and

Adam Sedgwick and ![]() Roderick Murchison were central in this endevour. Their work was soon taken up by others as well, and there developed during the early 19th century

a classification of strata according to the organisms whose fossils were found in them. Over the following decades it took on its present form MAK980528 MAK110419.

Roderick Murchison were central in this endevour. Their work was soon taken up by others as well, and there developed during the early 19th century

a classification of strata according to the organisms whose fossils were found in them. Over the following decades it took on its present form MAK980528 MAK110419.

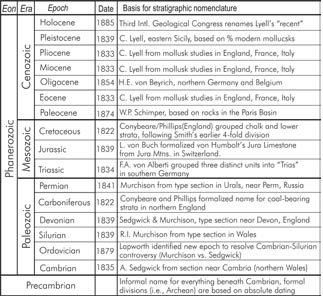

The various periods were named after geographical regions were periods were representative stratigraphic sequences could be found. Thus Cambrian is from Cambria, the Roman name for Wales, and the Ordovician, and Silurian periods were named after ancient Welsh tribes. Devonian is from the English county of Devon, and Carboniferous - Coal bearing - is simply a Latin adaptation of "the Coal Measures". The Permian was named by Murchison after the Perm region in Russia (which to this day remains an important locality of middle and late Permian fossil tetrapods). Triassic was coined in 1834 by a German geologist Friedrich Von Alberti because of its three distinct layers —red beds, capped by chalk, followed by black shales— that are found throughout Germany and Northwest Europe, called the 'Trias'. French geologist Alexandre Brogniart named the Jurassic after the extensive marine limestone exposures of the Jura Mountains. The Cretaceous (from Latin creta meaning 'chalk') as a separate period was first defined by Belgian geologist Jean d'Omalius d'Halloy in 1822, using strata in the Paris basin and named for the extensive beds of chalk (calcium carbonate deposited by the shells of marine invertebrates). The famous white cliffs of Dover are representative of these same strata. However, Tertiary and Quaternary were retained from an earlier terminology, reflecting the order of rock strata, although Primary (for Precambrian) and Secondary (for Paleozoic and Mesozoic) were discarded, or applied to the Paleozoic and Mesozoic (see diagram right). The Cenozoic was divided by Lyell into epochs such as Eocene (dawn of the recent), Miocene (less recent), Pliocene (more recent) and so on, depending on the proportion of modern mollusc shells found in these strata.

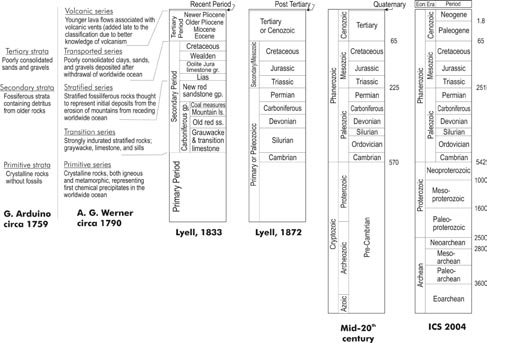

Date of nomenclature for the phanerozoic geological column. From The Historical Development of the Old-Earth Geological Time-Scale ( Creationist website) |

From 1830 to 1833, Charles Lyell published his multi-volume work Principles of Geology, which, building on Hutton's ideas, advocated a uniformitarian alternative to the catastrophic theory of geology. Lyell claimed that, rather than being the products of cataclysmic (and possibly supernatural) events, the geologic features of the Earth are better explained as the result of the same gradual geologic forces observable in the present day, but acting over immensely long periods of time. These ideas would strongly influence evolutionary thinkers such as the young Charles Darwin.

By the 1840s, the outlines of the geologic timescale (right) were becoming clear, and in 1841 John Phillips named three major eras, based on the predominant fauna of each: the Paleozoic, dominated by marine invertebrates and fish, the Mesozoic, the age of reptiles, and the current Cenozoic age of mammals. This progressive picture of the history of life was accepted even by conservative English geologists like Adam Sedgwick and William Buckland; however, like Cuvier, they attributed the progression to repeated catastrophic episodes of extinction followed by new episodes of creation. Unlike Cuvier, Buckland and some other advocates of natural theology among British geologists made efforts to explicitly link the last catastrophic episode proposed by Cuvier to the biblical flood.

Chart illustrating the division of geological time about 1840, with modern equivalents (note taht Precambrian is now rarely used). Important formations are shown in the left-hand column. The major divisions recognized about 1790 are given in the second column; but it should be noted (a) that much more detailed divisions were being applied at this date to particular regions, although correlation between them was uncertain, and (b) that the categories "Transition" and "Primary" have no exact equivalents in later schemes, because they included slightly or highly metamorphosed rocks of many ages (though predominantly of the ages shown). From From Martin J.S. Rudwick, The Meaning of Fossils (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1985), p. 213, via Historical Developments in Geology, Paleontology, and Cosmology by Terry Mortenson (Creationist website) |

Until the discovery of radioactivity in 1896 and the development of its geological applications through radiometric dating during the first half of the 20th century,) which allowed for more precise absolute dating of rocks, geologists and paleontologists constructed the geologic table based on the relative positions of different strata and fossils, and estimated the time scales based on studying rates of various kinds of weathering, erosion, sedimentation, and lithification. The ages of various rock strata and the age of the Earth were the subject of considerable debate.

The first geologic time scale was eventually published in 1913 by the British geologist Arthur Holmes. He greatly furthered the newly created discipline of geochronology and published the world renowned book The Age of the Earth in which he estimated the Earth's age to be at least 1.6 billion years.

In 1977, the Global Commission on Stratigraphy (now the International Commission on Stratigraphy) started an effort to define global references (Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points) for geologic periods and faunal stages. The commission's most recent work is described in the 2004 geologic time scale of Gradstein et al, which has since been further modified (e.g. Walker & Geissman 2009)

Chart showing development of geological timescale in England. Modified from Rudwick (1985) and Gradstein et al. (2004). From The Historical Development of the Old-Earth Geological Time-Scale by Dr. Terry Mortenson (although a Creationist website the first half of the article (the historical review) is quite useful) |

Links: History of Geology blog by David Bressan - best on the web; http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/geohist.html Changing Views of the History of the Earth, very uyseful detailed essay and historical timeline by Richard Harter (1998); Early ideas of the age of the Earth (study notes - Pamela J. W. Gore); Development of the Geologic Time Scale; THE DISCOVERY OF GEOLOGICAL TIME - Religious and philosophical inputs to geochronology - by David J. Tyler - very interesting on-line article; Timeline - chronicles some of the major events in the history of paleontology and biology; History of Geologic Time Scale at UCMP. For various early 20th century geological time charts which include dating estimates that are more than an order of magnitude too small, see Laelaps - The times they are a-changin' by Brian Switek.

| Page Back | Page Top | Unit Up | Unit Home | Page Next |

content by MAK110418, long quotes from Wikipedia.